01 August 2017 Consultancy.uk

http://www.consultancy.uk/news/13776/us-income-inequality-rift-continues-to-widen

Income inequality has been a thorny issue in the United States throughout the previous century. Now, financial disparity seems once again to be growing, with a new study painting an uncertain future for many in the country.

The US national debate has been absorbed over recent months with the Roman circus that has been the media storm surrounding Donald Trump’s controversial Presidency, with most of the discussion focused almost exclusively on alleged collusions between the new White House administration and Russian cyber criminals. Amid the continued uncertainty surrounding the current White House, the economy has continued to grow, in spite of growing global concern. However, the growth seems to do little to assuage growing inequality in the United States, an issue which in a more conventional Presidency might have come to the fore sooner.

The divide between rich and poor has debatably never been greater in the USA, and certainly never so emphatically illustrated, with a billionaire business magnate spending public funds heavily on trips to Mar-A-Lago, while attempting to dismantle a health care system implemented by the previous administration to give health insurance to society’s most deprived. In a new report from McKinsey & Company, titled ‘Making it in America’, the research arm of the consultancy firm lays bare the changing dynamics for labour income in the US. The research explores changes over the past five decades, as well as considering the future for the country’s working-class and middle-class populations in Trumps America – while drawing the troubling conclusion that hard work does not unconditionally pay dividends, even in the self-styled land of opportunity.

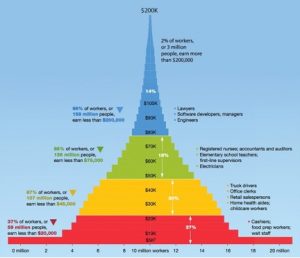

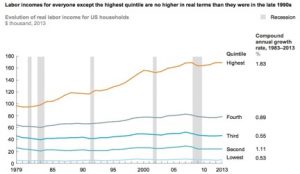

In spite of the claims of the keepers of the flame of Reaganomics, trickledown theory economics appears to have failed to benefit anyone but the wealthiest Americans, having first been implemented in the 1980s during former actor Ronald Reagan’s two term Presidency. Income for the lowest two thirds of the US population has been effectively stagnant since the recession in 1983, even falling in real terms relative to the troubled late 1970s. Income for the highest quintile, however, has grown in leaps and bounds since the early 80s, at CAGR 1.83%, with income for the group increasing more than the total income of fourth quintile to around $160,000.

McKinsey’s researchers note that some groups have taken harder hits than others. While much of the new work since 2010 has gone to lower wage industries, the vast majority of new hires – 99% of the 11.6 million jobs added from the bottom of the recession through to 2016 – went to those whom have at least some college education – while 77% of the 7.2 million job losses in the recession affected those with a high-school diploma or less. A lack of job creation for higher paid “white collar” jobs has seen graduates increasingly forced to compete in “blue collar” sectors, leading to those without paper qualifications increasingly unable to land unskilled work, while many of the ‘new’ jobs are placed in the hands of those whom are overqualified for them, presenting a huge waste of talent in both directions. Under 35s meanwhile, who tend to have a college qualification and are subsequently lumbered with student debt, have seen their real wages shrink significantly since 1983. With graduates now less able to repay their loans, national student debt has lept to $1.34 trillion in 2017, from $400 billion in 2005.

Mind the gap

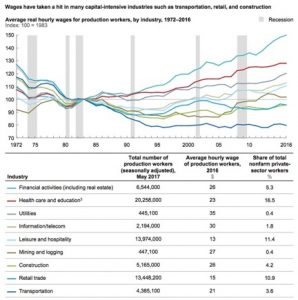

While wages across have remained stagnant across most income quintiles for the past almost fifty years, various industries have seen wages decrease over the period since 2983 – particularly those in capital intensive industries.

The biggest drops were noted in transportation, retail trade and construction. Retail trade remains one of the country’s largest private sector employment sectors, at 10.9% of the total working population. Unsurprisingly perhaps, financial services have seen by far the biggest increase, almost doubling its Index score, while the sector employs around 5.3% of US private sector workers.

The study suggests that the structural conditions, which affected real wage growth even before the recession following the financial crisis, are set to continue to affect real wage growth for workers, even if recovery continues. These conditions pertain largely to technology shifting productivity from labour intensive processes to knowledge intensive processes; in addition, competition has heated up in various sectors, while the number of potential employees has increased – creating an increasingly uneven playing field between labour and capital, which has affected wages and employment levels for lower-skilled workers.

In addition, the firm notes that capital-light industries tend to be out performing capital heavy industries, while across the board the research points to “superstar” companies, gobbling large amounts of profit, creating rich rewards for their workers, while depleting the rest of the industry of success. A recent report into corporate profit found that there is considerable profit inequality between firms, 10% of corporate entities hover up 80% of profits.

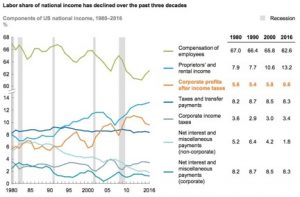

The increased pressure on labour is reflected in its declining share of national income – even while the higher income quintile has seen its share of total labour income increase significantly. In total, compensation for employees has fallen from 67% of total income in 1980 to 62.6% in 2016. Meanwhile, corporate profits have skyrocketed, up from 5.6% in 1980 to 9.6% in 2016.

Aside from facing stagnating wages, various aspect of necessary costs for workers have continued to rise. Proprietors’ and rental income has also increased significantly, from 7.9% of total income to 13.2%, while house prices have become unaffordable for large numbers of US workers. As such, rent and basic utility bills now eat up around 50% of the income of the lowest paid workers in the US.

American Dream

Workers are finding a range of barriers to gainful employment, including increased skills mismatches, fewer pay-roll positions as companies increasingly outsource, utilise contractors or use temporary workers. In addition, companies have started to hollow out benefits, while poor health – and no access to quality insurance – means that many workers face internal and external barriers to employment. Switching jobs too has become more difficult with ‘non-compete’ agreements limiting their options, as well as changes in market dynamics to urban areas, while moving has become increasingly difficult, the number of individuals relocating in a given year, is near 12%, down from 20% in the mid-1960’s.

The research notes that the future for many US workers, particularly on low incomes, is relatively bleak. In line with trends across the Western world, the market is moving toward less secure work, from outsourcing to contracting, is set to see 32 million that undertake independent work as their main income. This group has no benefits, and is often not paid the full cost of their labour – reducing their ability to save for retirement, illness and other areas in which nominal workers have protection from risks. Particularly the low-skilled in this group are set to find life increasingly onerous.

In addition, new forms of automation, which boast lower costs and higher productivity, have the potential to significantly affect employment levels within various sectors. While in the UK recent projections suggested AI may only create jobs to replace 19% of the jobs it ends, this figure could be even higher in the US – particularly for low-skilled, physical labour positions. Accommodation and food services, manufacturing and transport and warehousing, areas that represent a large segment of the labour economy, could see more than 60% of current activities automated over the coming decades.

The firm notes that there are looming questions for the US, particularly as inequality as such is set to rise, while the country’s major infrastructure continues to show signs of decay. While the need to invest in infrastructure could conceivably create an employment boom in the country, little movement has so far occurred to actually realise that, while the pay and conditions of any such work may well fit with the national trend that will see the subsequent labour created valued excessively lowly anyway.